“Does black and white landscape photography still make sense?”

This question was the core of my graduate research, and it was the spark that ignited Éire i Dubh Agus Bán, my most ambitious photographic project.

We live in an era in which color photography is the norm and in which the immediacy of the image often prevails over contemplation. My question was not purely academic: it was a personal challenge. I wanted to find out if the black and white landscape, in its essentiality, was still able to speak, excite, tell.

The origins of a choice: why black and white?

Black and white is not a nostalgic choice, but a conscious act.

I chose black and white because it eliminates the superstructure of color and restores the landscape to its primordial soul.

The absence of color becomes a universal language that allows us to focus on:

- Light, as a narrative element.

- Shadow, as a guardian of mystery.

- Form and texture, as traces of memory.

I wrote in my Visual Diary:

“This artistic choice conveys a sense of timelessness and mystery that invites the observer to a deeper reflection.”

Black and white has become, for me, a language of resistance: an invitation to slow down, to look beyond the surface, to get in touch with the true essence of places.

Inspirations: Adams and Salgado as masters and guides

In my research, two figures have been fundamental.

Their influence has gone far beyond the technical aspect; they have defined my attitude towards the landscape.

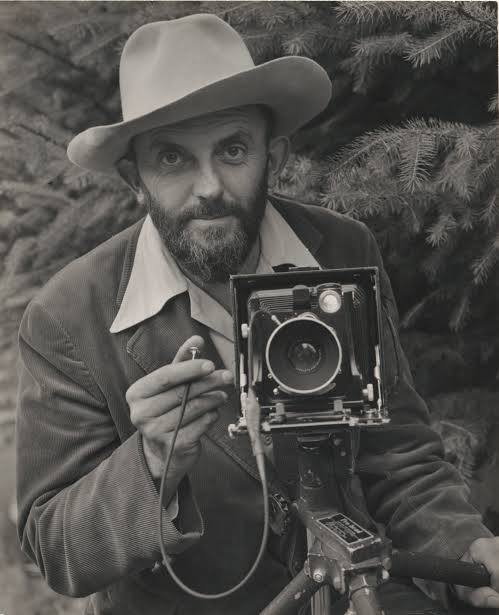

Ansel Adams

Adams was the model of technical precision.

Through the Zone System, he demonstrated that black and white landscape photography is a scientific practice as well as an artistic one. His meticulousness in exposure, attention to detail and ability to convey emotions through shades of gray were a beacon for me.

I wrote:

“The project is clearly inspired by the work of Ansel Adams, but it goes beyond a simple stylistic tribute, trying to create a unique visual narrative.”

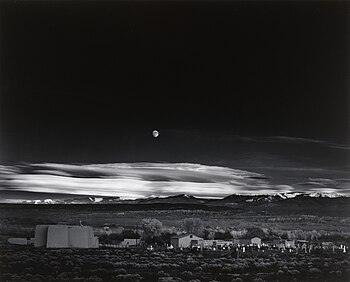

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941)

There Adams captures a moment of technical and emotional perfection. This is the level of rigor that I have tried to bring to my images.

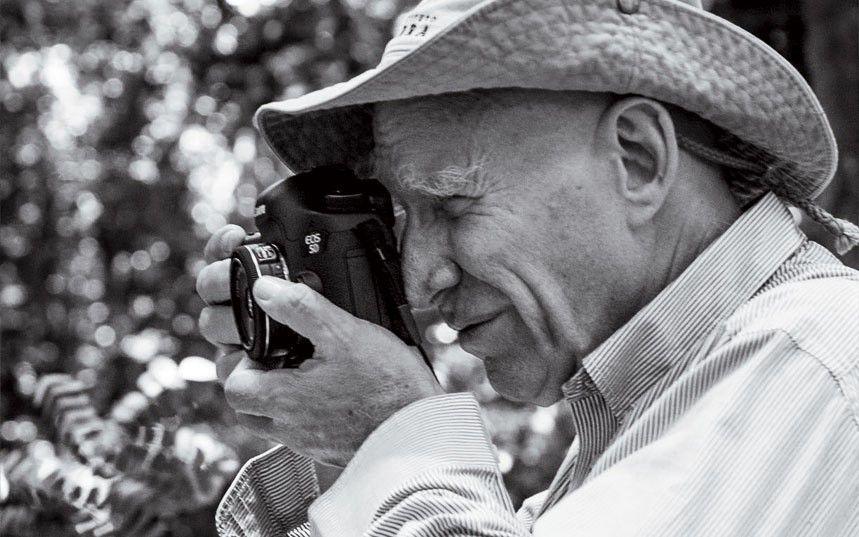

Sebastião Salgado

With Salgado, landscape photography becomes ethical narration.

In the Genesis series, Salgado narrates a majestic yet vulnerable, almost sacred nature. I studied his approach in depth to understand how to make the landscape visceral and human, while maintaining a respectful distance.

Antarctica Peninsula, 2005

An image in which nature becomes the protagonist of a silent revelation, something I wanted to convey with Éire i Dubh Agus Bán.

From theory to practice: landscape as an act of contemplation

I decided to test my reflections in the field, letting myself be guided by the places and extreme conditions of south-west Ireland.

I wrote in my diary:

“The project was born from a silent dialogue with the landscape, where every place is a border and a bridge: between light and shadow, between the human and the natural.”

Each photograph was carefully constructed, following a rigorous methodology:

Scouting, attentive to light and atmospheric conditions.

Compositional choices influenced by natural geometries, as explained in my tests on Ladies View, Beara Peninsula and Skellig Islands. Use of bracketing and HDR fusion to capture the entire dynamic spectrum of the scene.

Is there still a reason for landscape photography in B/W?

After months of research, study and fieldwork, the answer has become clear: Yes, there is still a reason to photograph the landscape in black and white. It is not a stylistic exercise, but an act of resistance to the speed of visual consumption.

Photographing in B/W means asking the audience to stop, to listen, to observe carefully and to get in touch with something profound and universal.

I wrote:

“I want to challenge those who observe my photographs to see beyond the visible, to connect with the deepest essence of the places represented.”

Towards a new way of seeing the landscape

Éire i Dubh Agus Bán is not just a photographic project. It is an attempt to rethink the role of the landscape photographer today:

- A witness, who observes without forcing.

- An interpreter, who translates without overwriting.

- An inner traveler, who transforms every shot into a moment of introspection.